↓

When the cinematograph appears, Thomas Edison and the Lumière brothers achieve a feat: capturing and reproducing reality in motion through a recording and projection device directly descended from photographic equipment. The year 1895 marks the beginning of an era of renewal in image and entertainment culture, thanks to a small hand-cranked box that would become, in the hands of Georges Méliès, a revolutionary fiction factory.

However, for some, this birth comes after 34,000 years of gestation during which cinema was a dream, a desire touched upon and expressed by humans through art, philosophy, and scientific inventions. This dream was to capture a shadow and give life to images, to satisfy this human desire for storytelling. Here is the history of this journey towards the invention of a universal writing of movement that has allowed us to see the world in double.

Cave Wall Projection

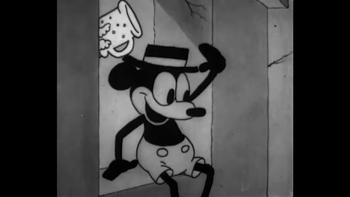

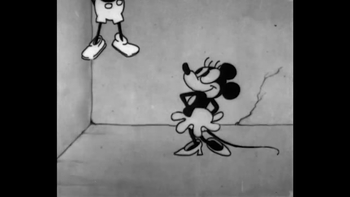

Let's go back to the time of great cave paintings to find the origin of cinema. The Paleolithic hunter-artists drew on cave walls a dynamic bestiary, engaged in action and reproduced through precise observation. They thus took the first steps toward kinetic art by inventing the first figurative art and the first attempts at representing, or even synthesizing, movement. Marc Azéma, a prehistorian specializing in cave art, demonstrates in his book La Préhistoire du cinéma. Origines paléolithiques de la narration graphique et du cinématographe the extension of Will Day's intuition from 78 years earlier when he indicated in an unpublished book: 25,000 years to trap a shadow that cinema's origins could be found in the Altamira frescoes (25 BC).

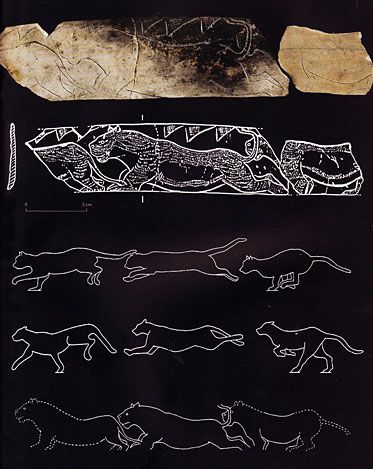

Marc Azéma's research first demonstrates that 40% of cave drawings represent animals in motion. This movement is depicted through superimposition or juxtaposition of successive images. Thus, its recomposition is generated through superimposition or frieze.

Although the kinship of these images with sequential animation techniques of cartoons seems more obvious, the connection to cinematography might indeed seem dubious. What seems certain, however, is the attempt to reproduce movement - and thus simulate life - by these artists who attributed a fundamental function to light in the staging of images. Diffuse and flickering, produced by torches or fires scattered at the foot of the walls, it helped bring painted and engraved motifs to life by playing with shadows created by the rock's relief. Thus, Marc Groenen has demonstrated that Paleolithic artists played with light to hide and reveal motifs, produce a movement effect, and simulate the life of drawings through luminous vibration.

Mystery remains regarding the use of these images and the spectatorial modalities of cave art. Many hypotheses exist, including one suggesting that the decorated walls were supports for mystical dialogues and prehistoric legends. But did these shows only mobilize spectators' gaze or did they also solicit their hearing? This is the question musicologist Iegor Reznikoff asked himself. Through his experiments, Reznikoff managed to demonstrate the association between the acoustic qualities of certain cave areas and the location of frescoes. Paleolithic artists therefore very likely matched their graphic choices to the resonance powers of spaces that we can imagine as places for oral tales, spiritual and shamanic ceremonies, or simply shadow and light shows staging animals in action accompanied by commentary and sound.

Marc Azéma goes even further, declaring that Paleolithic humans already composed the essential visual and narrative grammar of cinema. They used shot scales, focalization, and movement by integrating the spectator's gaze into the scene. They spatialized actions for narrative benefit, as if it were a primitive form of editing. For example, he takes the feline fresco from Chauvet cave, which, over 15 meters long, represents a hunting scene of rhinoceros by a pack of lions. The scene opens with a group of felines lying in wait, observing their off-screen prey in the distance. Prey that could be the spectators of the action themselves, that is, the cave visitors. These felines are signified by parts of their bodies, through synecdoche, comparable to close-ups and/or medium shots. They form a significant introduction to the following parts, which relate the charge and killing of prey by predators. This complex graphic composition reveals an effort at dynamic narration that seems to demonstrate that Aurignacian Homo sapiens knew how to graphically tell stories on one hand, and that the applied grammar announces filmic syntax.

.jpg)

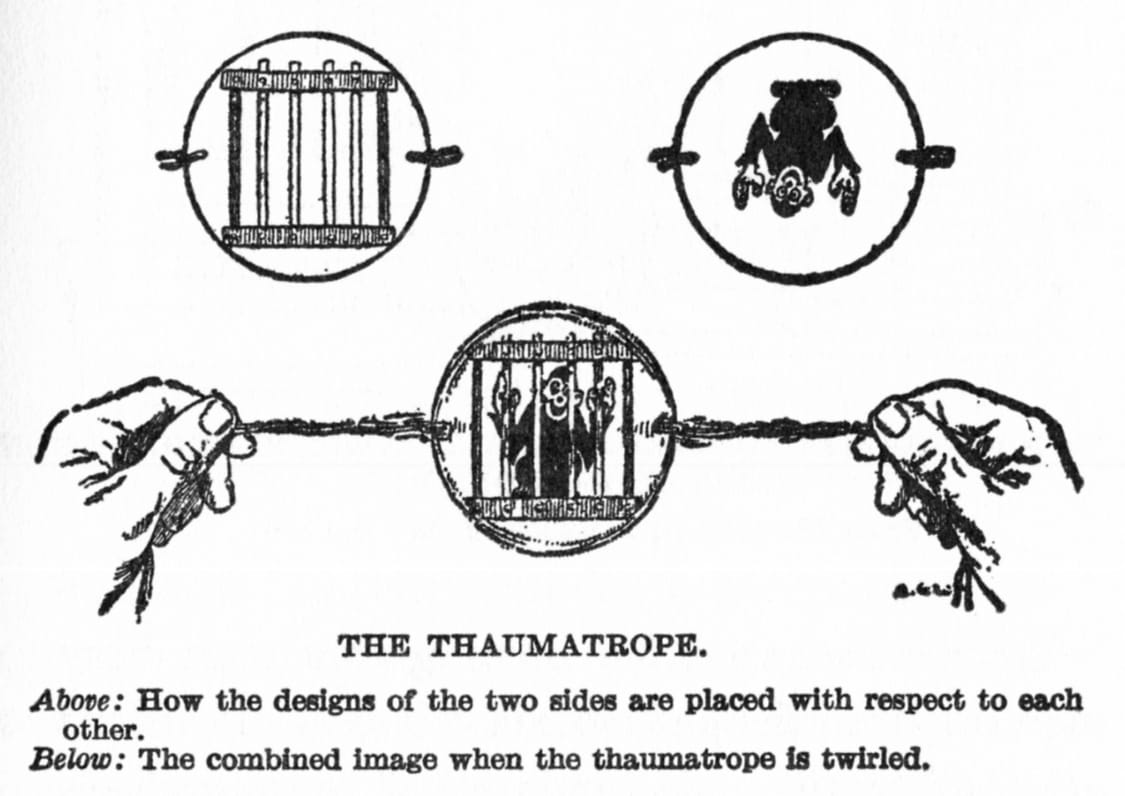

Paleolithic men and women also had their optical toys through which they generated the illusion of movement. In the archaeological site of Laugerie-Basse, a bone disc caught Florent Rivère's attention. It contains on its face a living chamois, on its reverse, a dead chamois, and in its center - where the animal's heart is located - a hole. If a thread is inserted, the disc, when spinning, reproduces in a brief movement the animal's passage from life to death. This is how homo sapiens invented the “thaumatrope disc” to visualize mini-stories depicting different actions such as hunting acts.

These demonstrations faced some criticism, accusing Marc Azéma of teleology, particularly in cinema circles for his retroactive vision of cinematographic art. Writing the history of prehistoric cinema risks approaching practices from an immeasurable past through the lens of contemporary advances. However, what these discoveries reveal is a prehistoric desire to write a story in motion. If we take cinematograph (writing of movement) in its primary etymological sense, then these primitive representations of animals in motion can be considered as cinema in an embryonic state. ::

Scenes of daily life in Pharaonic times

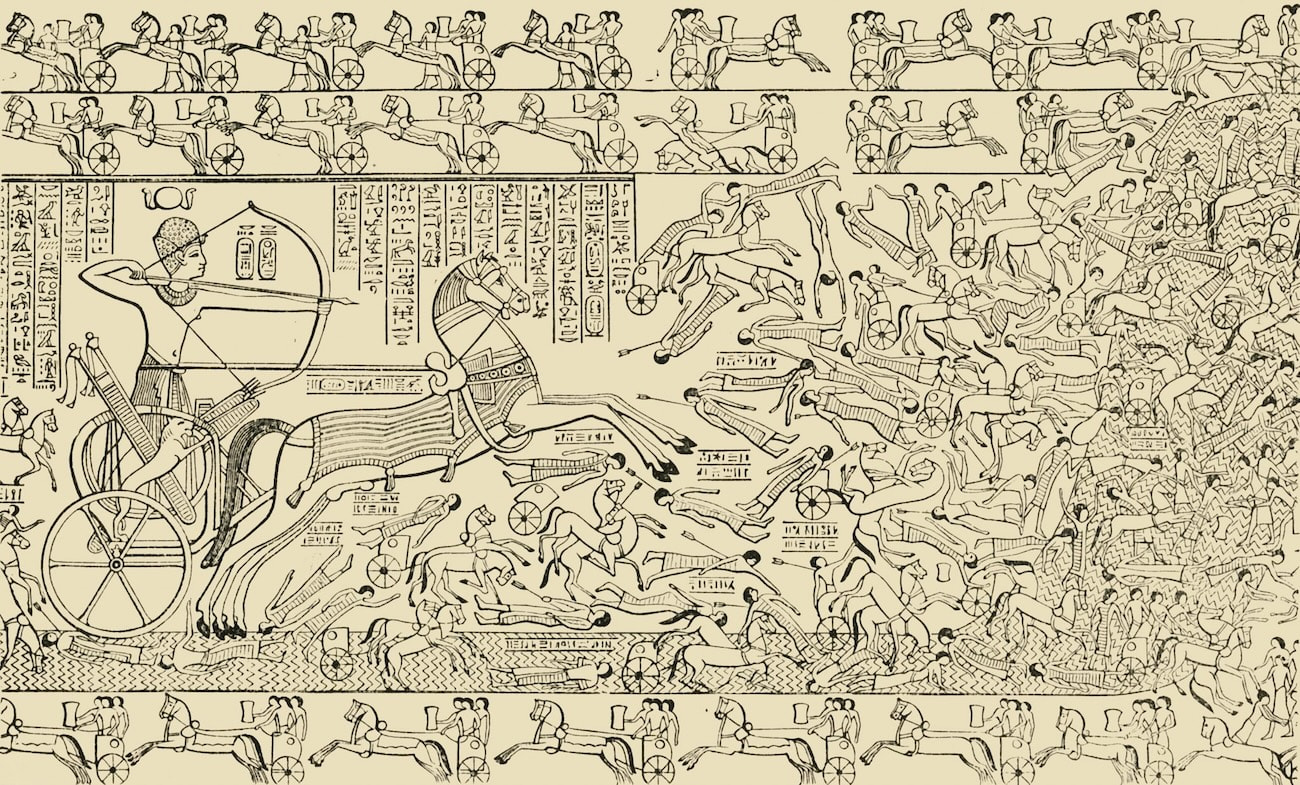

While it seemed to us that nothing could be more static than a hieroglyphic Egyptian, artists left the eternal trace of this quest for movement on the walls adorning the tombs and on the surface of papyri. Movement as represented in ancient Egypt is broken down to account for gesture or give a sense of dynamism. It's an effort of precision from a civilization inclined to record and catalog the smallest detail of things. Thus, the Book of the Dead or the walls of the Tomb of Beni Hassan could constitute the remains of a potential cinema. This is what Christiane Desroches Noblecourt suggests in an article titled Film and Screen in the Time of the Pharaohs published in 1949. The Egyptians during antiquity didn't really have paintings or sculptures for artistic purposes, but hieratic works or scenes of various registers aimed at evoking movement by breaking down actions; which constitutes “the film strip itself.” See here this example of movement generation despite the fixity of elements: The Battle of Kadesh opposing Ramses II to the Hittites. One of the rare great paintings that Egyptian Antiquity left us following the Amarnian artistic renovation (end of the 18th Dynasty). “The spectator” according to Christiane Desroches Noblecourt, witnesses “the heat of a strongly engaged action.”

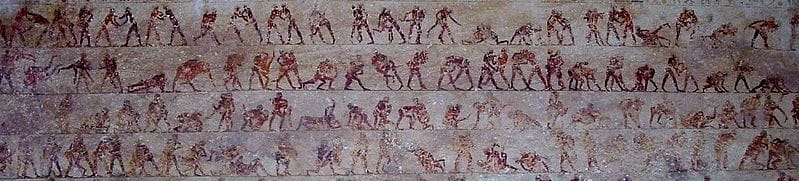

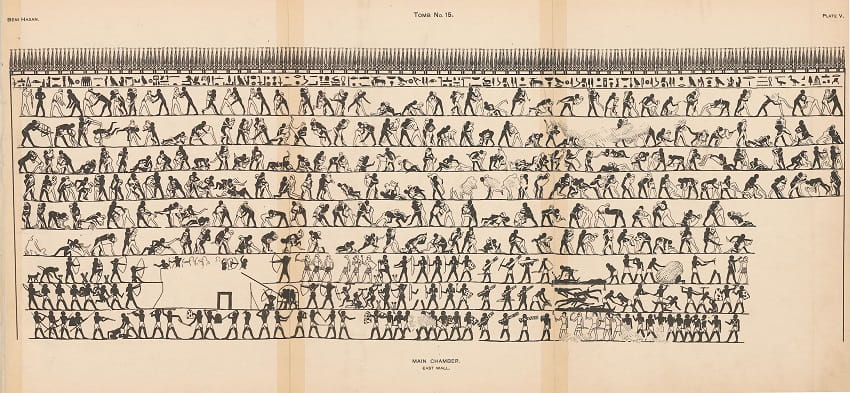

Located on the right bank of the Nile, the village of Beni Hassan contains a necropolis of rock-cut tombs from the 11th and 12th dynasties belonging to the ancient city of Menat-Khufu, birthplace of Pharaoh Cheops. There are 39 tombs carved into the rock, and among them, about a dozen are decorated with paintings that mainly depict scenes of daily life. For example, the daily activity in a pottery workshop or this surprising fresco in the tomb of Khety. Created between 1991 and 1926 BC, it represents the movement of two wrestlers broken down into a succession of actions arranged along six parallels, that is, six ground lines. We discover the sequential unfolding of an action, in the most minimalist display on entire walls of the tomb.

Christiane Desroches Noblecourt also mentions the dancer from tomb 15 who, if we hypothesize that the scene does not represent five but a single woman performing a graphically decomposed dance step, would then be a primitive formulation of movement synthesis.

In Search of Lost Gesture

The ancient Greeks were less focused on comfort than beauty and possessed a deep artistic sense. The Greek language is musical, composed of short and long syllables whose succession created rhythm and suggested melody; hence the importance given to poetry. It would also appear that they were a people of dancers. The dances were multiple, varied, and practiced on many occasions. We know this because we have numerous testimonies today, both written and graphic, as demonstrated by Germaine Prudhommeau. According to her, ancient vases bear the imprint of dances, now lost, and present clues to rediscover them.

Before her, research had been initiated by Maurice Emmanuel in his Treatise on Ancient Dance written in 1895. He held the same postulate: on the figured monuments of ancient art, certain silhouettes constitute photographic reproductions of moments belonging to a past reality. The figures represented in dance postures would therefore be frozen in a precise moment, and artists would have focused on decomposing their movements. However, the order is not given automatically, and the snapshots are mostly isolated from the rest of the gesture. If we reproduce them identically, we can then reconstruct them using a new tool: chronophotography. Maurice Emmanuel would therefore ask dancers to reproduce the snapshots from ancient works and amphoras and photograph them. With the help of Étienne-Jules Marey, this famous biologist who developed a tool to break down movement for better study: he would reconstruct the lost dances and profoundly influence dancers like Loïe Fuller, Isadora Duncan, and Eva Palmer.

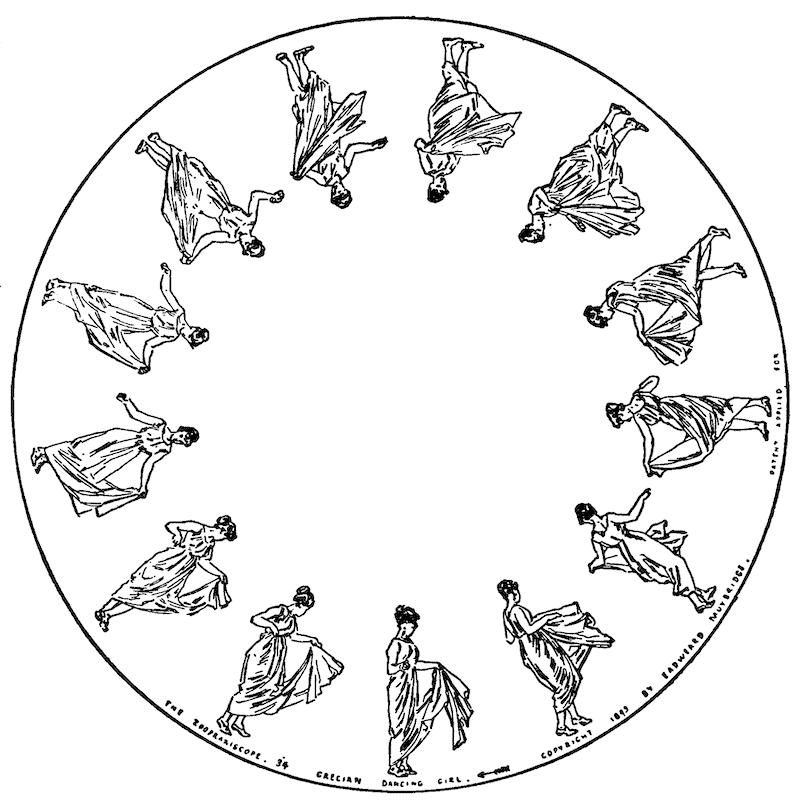

Germaine Prudhommeau thus conducts her experiments from ancient iconography, reduced to a single size comparing the entire work and the different isolated figures. In some cases, she says, photographic negatives of the characters must be provided, as some cultures and civilizations like to blur the tracks. Passionate about cryptography, natives of the Mediterranean basin do not hesitate to place characters in a misleading order. She then sorts the characteristic moments and suggestive moments, then assembles them according to the principles of classical dance, reputed to be close to ancient gestures. She initially draws inspiration from Muybridge's process. On a rotating circular plate, she arranges the different figures drawn from the same object one after another in a direction deemed coherent and anatomically feasible. When the plate turns, these different postures must overlap. Greek artists would indeed, according to her, have represented certain postures of the same movement on the same vase rather than the entirety of its sequence. She then creates a series of films to refine her research in the manner of stop-motion, edits them, and projects them, thus bringing these vanished dances back to life.

Unfortunately, all his films burned in the fire at his house in the 1970s. We can only imagine what they might have been like. Maurice Emmanuel, Louis Séchan, Germaine Prudhommeau, and many others championed a reconstructionist approach that was heavily criticized from the 1990s onwards but which, for our purposes, allows us to uncover another testimony of cryptographic writing of movement on ancient vases.

In the beginning was shadow and light

“Cinema is an idealistic phenomenon,” said André Bazin, “The idea that men had of it existed fully armed in their minds like in the Platonic heaven.” For good reason, Plato relates at the conclusion of The Republic written in the 4th century BCE this fable told by Socrate to his disciple Glaucon :

"Individuals held prisoner in a cave perceive, since the beginning of their existence, only a faint ray of light through which guards wave objects and wooden puppets. Only the cast shadows of these puppets on the cave wall are visible to them and constitute their only knowledge of reality. Their world, in sum. One day, one of them is freed from his chains and sees a light at the end of a steep, ascending path. He moves toward it with difficulty and after considerable effort, manages to exit the cave. For the first time, he sees in the bright sunlight reality as it presents itself. He recognizes a bird in flight, while before he only knew its image. He accesses the world of ideas. Then, he returns to the cave to share his discovery and free those who remained in the shadow and ignorance of the cave. Upon learning that their world is only illusions and their knowledge merely lies and artifacts, the men are devastated and refuse to believe in this world that might exist above them. So, they kill the clear-sighted man and turn their backs on the path to knowledge."

This fable constitutes one of the great myths of Western thought and continues to prove its malleability as it offers multiple interpretations across many disciplines. However, as the title of the work indicates, it falls within a political field and questions our relationship with reality through the prism of perception. This is why André Bazin considers it as one of the ideational inventions of cinema. Four centuries before our era, Plato describes the projection device: through light, a ghostly reality moves before the eyes of immobile men who believe in the reality of what they see. For Plato, a metaphor of humans living in a society alienated by images. A metaphor for the spectator watching a film that takes on the appearance of reality but is nothing more than a spectral replica of the imitation of reality?

The Allegory in question serves Plato's argument that Aristocracy is the best political system: it's the famous power in the hands of those who have spent their lives thinking about great concepts. The philosophers, therefore. According to him, the world is structured by shadow and light: in the shadow, the sensible world; under the sun, the intelligible world. The sensible world is the real, concrete world that can be perceived through the senses. This world, similar to what the prisoners perceive in the cave, consists only of particular forms and imperfect copies of the Idea of each thing. The intelligible world is that of ideas, it is accessible through thought and contains the absolute forms and the very essence of things. It is accessible after many efforts and many hardships endured by the philosopher whose burden is to transmit these truths to men who, often, consent to keep their reflexive and ideological chains.

No doubt Plato would have pilloried cinema but praised propaganda films. Art should have only this function, he thought, to transmit the ideas of philosophers to change those of citizens. At work, this idealistic thought according to which art that manipulates the masses can thus change reality.

L'allégorie de la caverne runs through film studies far and wide as it introduces the concepts of imitation, reality, and principles of reality that are fundamental in filmic thought and in reflections about image in our society. It allows us to address themes of the double, the real, simulacrum, truth, and access to knowledge through the detour of imagination. But interest in this philosophical fable gained renewed momentum in the 90s with the explosion of Matrix inspired by the thought of Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) developed in Simulacre et Simulation (1981), Amérique (1986), or La Guerre du Golfe n'a pas eu lieu (1991) in the 1980s. ::

"19 BC: The Aeneid and the Virgilian Camera"

In 1958, Paul Léglise attempted to demonstrate in an essay that the first book of the Aeneid could constitute a vestige of pre-cinema and be subjected to film analysis.

Virgil (70 - 19 BC) was a Latin poet who lived during the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of Emperor Augustus's reign. He devoted the last 19 years of his life to composing this great national epic modeled after Homer's Iliad and Odyssey. It tells the prophetic rise of the Roman Empire through the narrative of Aeneas's trials.

Between the poet's pen and the reader's inner eye, the film.

In the realm of inanimate figurative art, film art manifests itself in poetry which, according to Paul Léglise, constitutes a performative visual language, translatable into cinematographic language. After all, if it seems perfectly natural to translate a work from Latin to French, then why not translate it from Latin to cinema? And this is what Virgil would have done: adapt Homer's literary work into film language. Analyzing the first book of the Aeneid, he asserts that the poet's aesthetic conception is fundamentally cinematographic; in how he strives to represent characters' vision, visually construct landscapes, and translate the movement of gazes as if it were alternately a subjective shot scanning a scene or a fractionation of scales comparable to editing. Had the ancient poet lived in the time of cinematography, perhaps he would have made an excellent filmmaker?

1958, the date this essay was written, whose premise had struck a chord but may seem risky and unconvincing to us today. 1958, spring of a new wave that turns its back on classicism and buries its authors. Perhaps Paul Léglise's gesture consists of this: elevating a fallen masterpiece to the heavens?

The Spectral Art of Cast Shadows

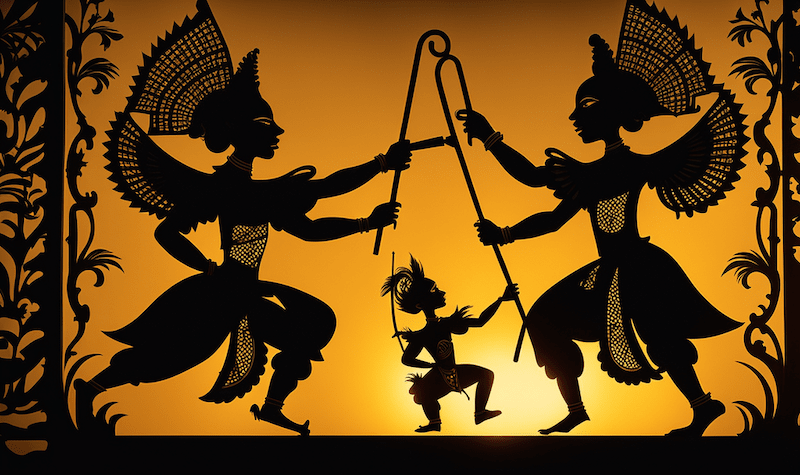

“The dream of projecting luminous and animated images on a wall or screen is, in human history, almost as old as the dream of flying,” writes Laurent Mannoni in a fascinating book titled The Great Art of Light and Shadow, Archaeology of Cinema, published in 1994. And for good reason, according to Will Day, the pre-history of cinema makes a stop in China and Indonesia in times so remote that it is almost impossible for us to date. Very popular in Asia, the most well-known forms of this type of show are Chinese shadow puppetry PiYing and Indonesian Wayang Kulit. They consist of animating cut-out silhouettes by projecting their shadows onto a screen from behind the theater. The luminous back-projection and filter effects formed by the screen ensure the beauty and finesse of movement while puppeteers manipulate these articulated flat leather heroes using thin rods.

In Indonesia, they developed around Bali and Java, offering village populations the opportunity to follow the adventures of heroes from popular tales and Sanskrit epics like the Ramayana and the Mahabarata. They played a major role in the expansion of Hinduism in the country before the arrival of the 9 saints and the spread of Islam. The Wayang Kulit has accompanied Indonesians for over a thousand years, who consider it entertainment, spiritual and moral guidance. The government still uses it as an important communication medium with populations living in sometimes isolated villages, while it simultaneously serves as a venue for social satire and criticism. The dalang is the storyteller who animates the hundreds of puppets needed for a Wayang Kulit show, modifying his voice and intonations for each character. This spectral art, which relies on screen projection and the staging of folkloric tales, offers a spectatorial experience that anticipates that of cinematographic projection. They at least fulfill similar functions in people's daily lives, gathering around a collective imagination by drawing from both traditional repertoire and contemporary events. But what shadow puppetry awakens is the connection that screen projection maintains with death. Among the powers attributed to cinema from the early days of its language formation and resulting reflections, is that of animating past time, achieving the illusion of life through movement, despite the stillness of the figure. Animistic beliefs updated in an era of strong invention and industrialization, due to the cinematograph's kinship with the magical art of phantasmagoria. The shadow is our spectral double, our inverted likeness without flesh and elusive. It is our ghost, in sum. ::

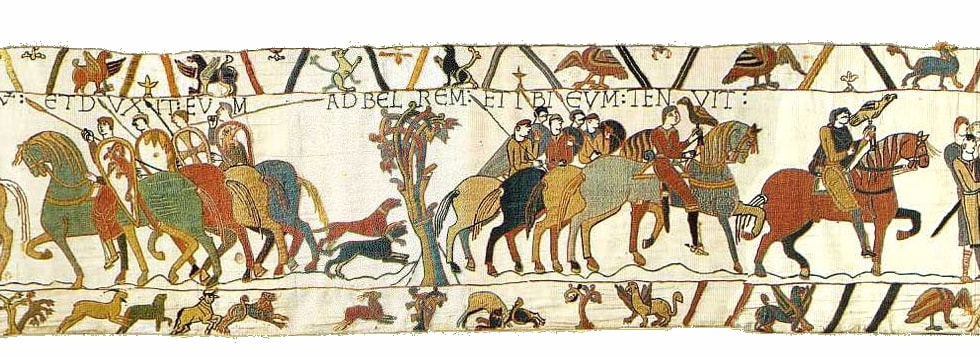

"1100: The Bayeux Tapestry, a propaganda film?"

Edward the Confessor, King of England, dies. Harold Godwinson - powerful English aristocrat - and William the Conqueror, fight for the crown on the battlefield of Hastings in 1066. Harold is killed there, the Duke of Normandy is enthroned, and to legitimize this seizure of power through arms and his enemy's perjury, William has the story of his prophetic victory embroidered on a long strip of linen. Thus unfolds across 70 meters of fabric, in a succession of harmoniously arranged actions, the legendary tale of the Norman Bastard.

Like most continuous-scroll friezes, the Bayeux Tapestry quite naturally reminds us of film. This is at least what some have tried to demonstrate while others placed it in direct lineage with comic strips.

For Marie-Thérèse Poncet, if a film is a plot or any subject unfolding in a sequence of pictorial shots whose presentation possesses what the ancients called “anima” - soul, life, then the Bayeux embroidery can be considered a film.

An animated strip before which the mobile observer's gaze moves from left to right, the tapestry brings together in a narrative breakdown the different stages of the legend according to the principles of editing. Comparable to the effect of film rolling, it forms a narrative unity from assembled sequences, giving each its own temporal unity and dramaturgy. This breakdown, which arranges the characters' actions more or less linearly, allows for telling a dynamic story and infusing it with an impression of life. We observe both wide shots and fixed scenes such as Harold's oath-taking, a crucial moment and starting point of the conflict; close-up shots of restricted actions, as well as occasional integration of movement. We also notice an ingenious management of time through the insertion of flashbacks within scenes when William the Conqueror sends his emissaries to deliver Harold. To infuse this temporal break, the strip suddenly reads from right to left. A medieval flashback depicting the Duke of Normandy seated, listening to an emissary revealing that Harold is held in Guy of Ponthieu's castle. Rhythm effects are thus produced by the decomposition of gesture, as shown in the photo above, reminiscent of the juxtaposition of images used by men in Paleolithic times (referring to the long frieze of horses at Lagrave) and Étienne-Jules Marey's chronophotographic shots. The sea crossing by boat creates a similar effect of rapid pace, which is also found in the melees at the heart of the Battle of Hastings sequence. We note a management of dramatic time made of some breaks and flashbacks, submitting to the largely illiterate people an appealing and accessible reading of a manipulated historical event. It is in this capacity that Michel Parisse, Marie-Thérèse Poncet, and Jean Verrier consider the Bayeux Tapestry to have been a propaganda film before the existence of cinematography. ::

Conclusion

Tracing the pre-history of a desire or the genesis of a cinematic language may raise the hackles of most film historians. It can be criticized for its lack of seriousness, its hypothetical and fantastical nature, and face accusations of teleology and hair-splitting. Would they really be wrong?

But was cinema the objective, the goal to achieve, the purpose of these human investigations into the writing of movement, or is it a crossing point for this desire, constantly mutating towards new forms of expression? “Cinema is dead!” as the saying goes. Impossible. Since it has lived since the dawn of time, it will live until the time of the last human beings.

Before the cinematograph, humans sought to reproduce movement in a dramatic relativity, specific to the story they wished to tell, attuning the canvas to their poetic feeling of a world they wished to translate, or to the audience they wished to convince. They begin a dialogue with death to bring it back to life, searching in the elusive shadow for a new understanding of their surroundings, or as Jean Epstein would say, a new love of the world. ::